Here we are again, standing around in an otherwise-empty parking lot at 3:30am. No lights but the glow of a far-off gas station sign and 10,000 signal notifications lighting up our phones. I can’t remember how many times I’ve been here in this weird waiting room of the revolution. Everyone here has circles under their eyes and jail support numbers written on their arms. Their hands are clutching cups of coffee that have been cold for hours. Their mouths are tense but their eyes smile.

So we wait. We wait for the police to arrive, for the action to start, for our friends to get out of jail. Our feet ache from standing on concrete, so we laugh, joking about our pets and the ridiculous thing the judge said. And the hours tick. And eventually, the train arrives and we block it, or the raid starts, or the prisoners walk out. But always, always, there is the waiting.

Once, someone asked me when the waiting would end. We had been defending a homeless encampment from raids for months. It was late October by now, and we sat on overturned buckets amid drifted leaves and small piles of trash, playing with the frayed ends of our sweaters. He was young, a first year college student with a bright red fleece and more flyers on a single person than I’d ever seen. “When is stuff going to happen?” he asked. “When do we get to take the cool pictures?”

The mainstream narrative on movement history has a specific type of go-to image. There is Rosa Parks sitting on the bus, draft cards and bras burning in a trash bin. There are photos of strikes, of speeches and sit-ins, of tense courtrooms and people confronting lines of riot shields with flowers and feathers and raised fists. These images are important. They are evidence of our history, of the breathtaking courage of generations of liberation fighters. They are glaring proclamations of what’s possible: the massive shifts that can happen, the kinds of risks we could take, the bravery and imagination that results when people rise up. They are tools and inspiration for our work. But they are not the full story.

When we freeze people in time, we flatten them. We take living, breathing people and make them characters in our comic books, superheroes we can idolize from a distance. I can’t count the number of times I’ve heard this story, mostly from white judges and educators: “Rosa sat on the bus and went to jail, and Dr. King said he had a dream. Then, after that, Black people were free.” Her entire life’s work boiled down to a split-second decision, a frozen, glorious image of sacrifice, and poof! Change happens by magic.

What Rosa actually did was so much harder. She was the head of the NAACP in her region. She trained for weeks at the Highlander Center in nonviolent direct action. She planned her action and went into it with discipline, even though she knew what would happen. She worked for years before and after for Black Liberation. Her work was not just that day, but a lifetime- thousands of hours and meetings and protests and strategy sessions. That day, too, was more than her protest. She was human. She woke up and got dressed. She took a lot of deep breaths. She stood with her bag in both hands at the side of the road. She stayed at the bus stop and waited for the bus to come.

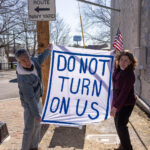

I wish there were more photos of the “unsexy” parts. The trainings, the tense meetings, and midnight supply runs. So often I meet activists who want to emulate the tactics of past movement heroes, who want to block a highway or chain themselves to a tree, who want to sit down and refuse to leave. And these can be great tactics, truely! But the problem happens when we emulate the tactics and not the work, when we become so focused on recreating a sexy, glorious image that we forget the strategy. Movements of the past worked because they organized, they built sustained mass non-compliance to the status quo. They worked because they made phone calls and knocked on doors and held months-long trainings. They worked because they did the boring, tedious, crucial work of relationship building.

The sexy pictures aren’t where the magic happens. Sure, they are dramatic and adrenaline-filled. Sometimes they make the world shake. But the real miracles are much more mundane. I have seen behind-the-scenes organizers work magic that I still can’t believe. When dozens of mass-action arrestees got stranded in different rural jail parking lots hours away from each other, I watched my friend orchestrate rides home from across the country. While a comrade and I sat in jail with $42,000 bail between us, another organizer drove for hours with a bag of cash to get us free. I’ve watched student organizers negotiate massive concessions on zoom calls of all places, watched mutual aid chefs brew straight-up potions. There, at the edges of the crowd, far away from the speakers and the cameras, look! A friend chops vegetables while deprogramming nazis.

One of my favorite people has never been arrested. He’s tall and thin and terrified of police. And yet, I’ve seen this man stand in renaissance-faire armor and send fascists running. I’ve seen him lurk deep in a swamp in the middle of the night, building lockboxes under a rain-soaked tarp. The light of his arc-welder flashes like lightning. He is covered in dust and cackling, eyes crazed like some warlock of the bog. In the morning, our lockboxes are sturdy and strong.

So I sit on a bucket with a different lockbox in my lap, half-decomposed pumpkins scattered around the camp. On the other side of the rusty dumpster, the soup tent sends up clouds of steam. The sunset glints on the windows of a yurt built from pallets and tarps amid the trees. Next to the tiny plywood church, some students on ladders hammer the roof onto the supply shed while others fill it with bike locks and sleeping bags. A police cruiser drives by, then away again. “Hey,” he says, “when do you think they’ll be back? When does the revolution happen?” I look over at the residents planting mums in the collective garden, at the barricades along the fence. I want to tell him that this is the point, not the raid that will come later, not the court cases or the news articles or the felony charges. This: the village that was supposed to be gone months ago. I want to tell him that the sexy parts are often when they hurt us, that the revolution is both magic and boring as shit. I look down at the dusty pavement. “Most of this work,” I tell him, “is waiting around in parking lots. You’re probably going to have to get used to it.”

Leave a Reply